I spent two months in Tanzania and less than a week of that time in the bush, but I was lucky enough to sneak a peek into true Masai life. I’m fully aware that it was an instant in the story of this tribe, just a little window into the Masai culture, but more than enough to be able to tell you this story. Because that’s all I’m aiming at, to tell you my educated perspective on a delicate subject. By no means I’m trying to be the voice of the Masai here. I asked many of questions to everyone that was willing to chat with me and I got to experience living with the Masai in the bush firsthand –a true once in a lifetime experience. I do hope you enjoy this cool tale, and you learn about the importance of indigenous peoples in the process.

First impressions of the Masai

*** I hate to start this uplifting tale about a beautiful tribe and lifestyle in a negative note, but please bear with me. I promise it gets better. Much better! And it’ll help you to be prepared if you visit Tanzania, because the Masai you’ll run into probably won’t be the amazing ones I’ll describe here ***

My first encounter with the Masai didn’t leave the best impression. The ones living in Arusha tend to be quite rude and really pushy selling stuff, and the ones in Ngorongoro are the kind that sit in the side of the road selling knickknacks and sending the children to beg for money. If the trip would have started in Zanzibar, probably my take would have been even worse, with the warriors openly telling tourists to buy their stuff so they can go drinking and partying. Don’t get me wrong, of course I’m not saying that all of them are like that, but those are the ones I ran into. It’s worth noticing that the pushiness is true of Tanzanian sellers in general, so you might feel like a walking dollar until you get use to it, and look pass it. Then you’ll start seeing that most people are actually nice, both Masai and other Tanzanians.

Still, probably I was expecting more ‘authenticity’, which in my white privileged brain means an indigenous tribe living as one with the earth, and not concerning themselves with trivial things, like money. But they do live in the 21st century, and they do need to make a living somehow. The situation with the Masai in Serengeti, Ngorongoro and other national parks and game reserves is a particularly big issue, and I went in-depth about it in this post. But, in general, they have been deprived of more and more of their ancestral land, so most are not able to continue with the tribal life they might want to have.

Still, even with all those considerations, it let me down a bit to witness the way they were behaving. As I went around the country the image didn’t change much. Pushy, rude, drunk. Luckily, I knew that’s not the whole picture. And I was wholeheartedly wishing that my take would change.

While planning my trip to Tanzania I ran into a video about the boma where a mzungu lives with her Masai husband, their son, and all his family. Stephanie –‘Mama Chachi’– was born in Germany, but found her true home in a small village in the center of Tanzania. If you’re wondering, ‘mzungu’ means white person in the country’s language, Swahili. And a ‘boma’ is the compound of huts where an extended family lives. Hers is composed of her father-in-law, his three wives, all their offspring, and their wives and children.

I needed to know more, so I went exploring her Instagram. She started her account to show the world how important the Masai culture and way of life are, to create awareness. I loved her message, so I reached out and she couldn’t have been nicer. “Come visit us”, she told me.

We met in Dar es Salaam, and after a day of beach time while I bombarded her with questions, we started the long journey to her village in the bush. At 5 o’clock we went to the bus station; at 6:15 we were on our way to Handeni. By 11:30 we embarked on the last leg to Lesoit.

The boma: living with the Masai in the bush

We arrived mid-afternoon to a bunch of happy, curious, cute kids, all demanding our attention. I spent the rest of the daylight hours tossing the younger ones to the air, playing football with the older ones, running around with them all, being shown the different huts, and taking photos. Well, letting the kids take most of them, being delighted taking turns to put the camera around their necks.

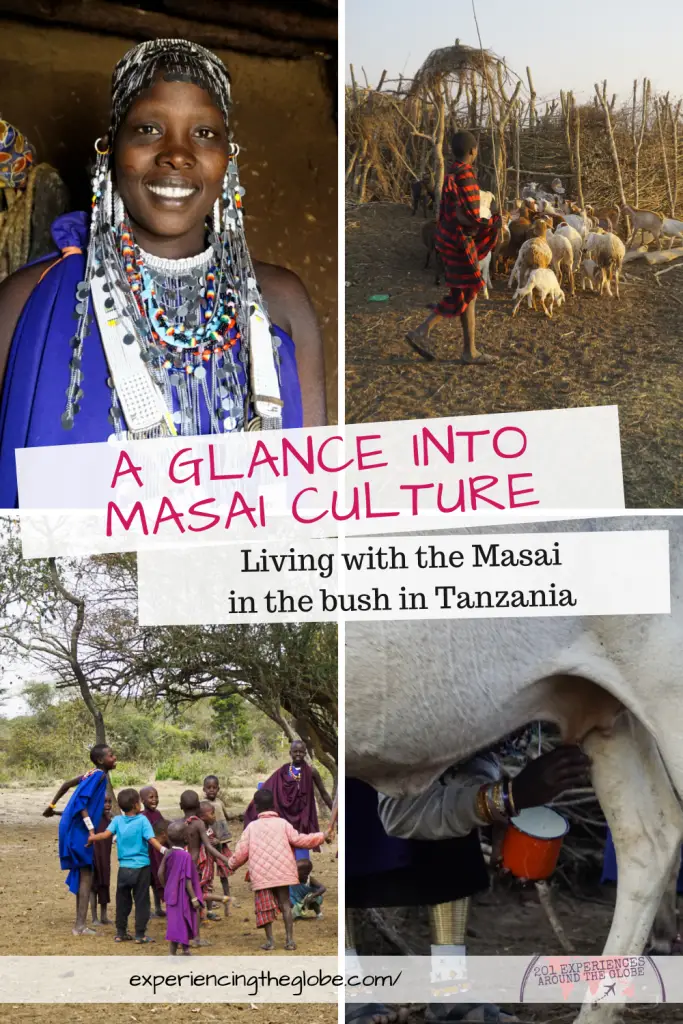

I met some of the adults, all welcoming me with open arms, even though we could communicate only by body language. One of them, Mulari, was the only one there at the time that spoke English. He surprised me with a few words of Spanish and even some of Croatian. I could easily tell he works in tourism while away from the village. In turn, all I learnt to say in Maa was ‘thank you’ and ‘good’.

Before sunset approached, the young men came back to the boma with their cows, goats, and sheep. After securing them in their cattle pens from the night terrors of the local hyenas, the women jumped to action. Armed with cups and pumpkin-carved containers, they made their way to the cows, put their heads against the cows’ side, and artfully milked them. They’d take the calves to the side and the mother cow would follow. The women took a cup or two of milk, and let the calves have as much as they need.

The sunset was welcomed by a bonfire over ginger tea. After playing a little more with the children and looking up at the stars until my neck started complaining, I called it a night. It was before 8 PM. I was officially living in the bush.

The boma, like most places in rural Tanzania, doesn’t have running water or electricity. There’s a long drop toilet for Stephanie and her guests, but the Masai just go around the bush. The water gets collected from the rain (during the rain seasons) or fetched from a nearby (ish) well, and it’s used carefully. A bucket gets warmed up for showers. Some boil it for drinking, some drink it straight away.

The houses are huts, of about 20 square meters, made of sticks bond together by a clay-like mix of cow dung, sand, and water. Inside there’s usually two beds, also made of sticks covered by a big piece of leather. One is for the man, the other for the woman and children. In one corner the milk is kept. In the middle there’s a shelf with pots, plates, and cups, and in front there’s space to make a fire, where the women cook. The huts have a couple of tiny windows –the only size that their house-making skills allow them to have. The homes are dark, but the people are openhearted.

Some Masai are trying to embrace the 21st century through the dwellings too. They hire Swahili people (non-Masai Tanzanians) to build cement houses. But this luxury is reserved only for those with money to spare. In my humble opinion, these modern ones have more light, but less soul.

Their livelihood used to be based only on cattle raising. “This is our bank account”, Mulari told me while I was looking at the goats and cows on their return to the village. But to buy more, and to indulge in modernity, nowadays the young men go to find work in the cities. And with it the traditional lifestyle is in decay.

The role of the men is to provide and protect. Upon reaching adulthood, a man is expected to take a wife, start having children, have another wife or two, have more children, and take care of his parents. This means that young men, before they turn 20, need to leave their villages and go to find work to support their family. Many of them not knowing how to read or write, sometimes not even knowing the country’s official language. This is not the case for every boy, but it’s usually true for the first-born. After him his siblings have it a tad easier.

The men at home, in the villages, keep looking after the cattle, while the women do pretty much everything else –from cooking and cleaning, to raising the kids, to fetching wood and water, to building the houses, to working in crafts for the men that go to cities to sell.

The Masai women

They have a hard life, dealing with a never-ending list of things to do, while enduring the husband that their fathers chose for them. But they don’t seem to be bothered: it’s the only life they know.

With roles specifically assigned and a life that full of hardships, is easier to understand polygamy. Why would you want a husband all to yourself, when you could share the responsibilities marriage brings with other women?

Life is never lonely this way. They might live in small huts, but life happens outside, with the community. The kids are raised together, with plenty of cousins to keep each other entertained. “In the west people live in big houses, but alone”, Stephanie told me, making it obvious that she’s happy with the path she chose living with the Masai, as a Masai.

Women’s role –beyond the chores that nowadays fill their lives– used to be as spiritual leaders. In today’s world it seems like there’s no longer need for that. The men handle politics, care for the cattle, and provide for the household, and the women are expected to do the rest. Money took the place of spirituality, leaving the women in search for the role they had in traditional culture in modern life.

I spent most of my time in the boma among the women. They welcomed me with open arms to their huts, tried to feed me every time something was being cooked, took the time to show me their utensils and explain how things work –they even showed me the traditional jewelry they wear for weddings when I enquired about it. And all of this without speaking a common language. Stephanie speaks fluent Maa, so she translated for me, but even when she wasn’t around, I was entering people’s houses like I was among my own family.

I could quickly tell that the women enjoy spending their days among other women. They do their chores with a smile; use their limited free time to sit in the sun and chat; and care about each other’s kids as if they were their own.

Having children is seen as the main role of a Masai woman. When their livelihood was based only on cattle raising, children were part of the family’s riches: they were going to be the ones taking care of the animals. But nowadays, since the Masai are looking for other sources of income, having many kids is becoming a burden. Even though contraception is available through the village’s clinic, some of the men are still not ready to let go of the tradition of getting their wives pregnant as often as they can.

I can’t make a judgment, nor do I pretend to voice something that only they could, but personally I have issues defending this aspect of the traditional way of life when I see that they would be better off with more women’s rights thrown their way.

Empowerment through sanitary pads

One simple but life changing example came from one of Stephanie’s projects. She sews cloth sanitary pads and distribute them to the girls and women in her village and around. The girls couldn’t go to school for a few days every month in fear of having stains in their clothes. The women were having problems performing daily activities thinking blood would run down their legs. No one talks about it, of course. As most issues related to women, it’s a taboo.

So Stephanie’s kits, composed of a underwear, a cloth pad, and some exchangeable liners –all washable and reusable, hence sustainable– had a huge impact. Women can now live a normal life every day of the month. A few pieces of sewed cloth had a profoundly empowering impact on the women of the community.

She told me she was hesitant at first to intervene, but she offered and the ladies were ecstatic. The traditions are not changed in any way, their hard lives got a tad easier, at least for a few days in the month. Some men are working to get a smartphone, I reminded her, the women using pads just got a basic need covered.

Stephanie set up a fundraise through GoFundMe where you can help out. With a 10€ donation a kit of underwear, 2 pads and 6 liners will be delivered to a Masai secondary school girl or women. This also provides a small source of income to the women in Stephanie’s boma, since they are the ones that do the sewing with her.

The Masai life

In Tanzania the hours of the day are measured in a different way. The counting starts at 6 AM. The first hour is counted when the day starts, with sunrise. Accordingly, 12 is our 6 PM, ending the day with sunset. The Masai life, like that of most living in the countryside, follows the sun too.

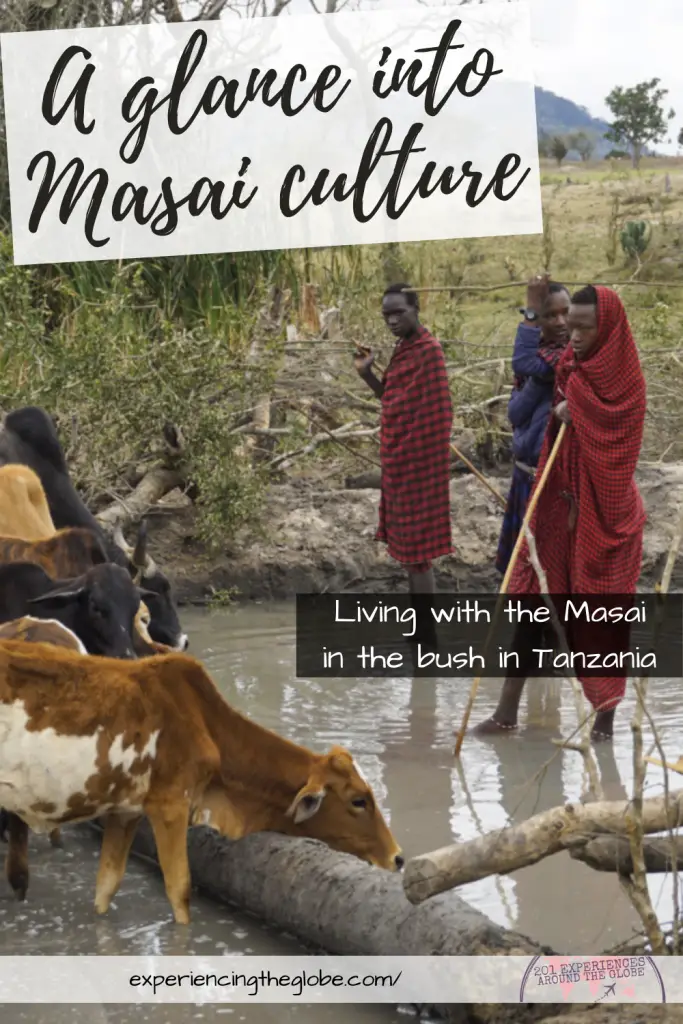

With sunrise the movement starts. The women milk the cows and make sweet, milky chai –tea made of milk, spices, and sugar. Because during my visit it was dry season and there wasn’t enough grass for the calves to survive, they were given extra feed, adding work into the morning routine. The calves and the baby goats and sheep stay in the boma while the adult animals are taken for feeding and drinking in the surrounding savannah. They have to walk for kilometers to make sure they have just enough to make it alive until the rainy season comes, and new grass grows with it. One morning during my stay in the boma Stephanie took me with the young warriors to see the waterhole where the cows were taken, a modest little stream, but all they have available at this time of the year.

They looked very comfortable whistling instructions to the cattle, helping themselves with a wooden stick that always accompanies Masai men. While the cows drunk, the men fetched some sugarcane, and artfully peeled it and cut it with a machete. Chewing the sweet juice gives them a punch of energy. They moved on and we returned to the village.

In the meantime, the women were busy, as always. One of them was patching her house up. She mixed cow dung, sand, and water, and spread it on her walls, like clay. I couldn’t stop myself from getting my hands dirty, so for an hour or so I ‘helped’ her. In all honesty, probably I imposed more than I assisted. But it gave me insight on how difficult the task is. She managed to make it look effortless, but –trust me– it’s not.

Other women were fetching water, firewood, and vegetables to cook. Almost every day they have to get at least one of these essentials. They make a humble –but full of work– breakfast, lunch, and dinner, usually consisting of ugali (a maize flour cooked with water dough-like stiff porridge), a vegetable stew, and chai. After feeding the adults and older boys that go off with the cows, sheep, and goats, they feed the many children, and wash up all the pots, plates, and cups. Even if their day started at 6, they don’t get a break until after lunch.

The few hours they have in the afternoons before the men go back are spent in the sun, catching up with the other women. Some also do crafts. A few work on the pads, others make jewelry –both to wear and to sell. And then the work starts again. Feeding everyone, milking the cows, washing up.

The boys come back around 4 o’clock with the goats and sheep. They are let to roam around the boma, while the babies run to their mothers for feeding in a commotion of ‘baas’ and ‘maas’. Walking around them (and petting the babies!) became my favorite time of day. Before 6 o’clock the goats are led to their fenced home (where they are safe for the night), before the young warriors come back with the cows. They’re also secured for the night, and the women milk them again.

The day starts wrapping up with the young kids making a bonfire and enjoying the warm while the last rays of lights give way to the stars. They eat and go to sleep. By 9 o’clock all that can be heard are the animals mooing and bleating. Which is, oddly, a lovely lullaby to fall asleep to.

The Masai children

The children grow up free. They run barefooted around the village, in their cute Masai jewelry and attires, mixed with hoodies or sweaters that have seen better days. Receiving little attention from the adults, they entertain themselves. They play with the sand and with makeshift toys. During my visit, they proudly showed me two balls made of wrapped pieces of plastic. I played football with them, and then (when they outbeat my energy) watch them play for hours. They look genuinely happy with this upbringing.

Few of them go to school. The education system in the country leaves a lot to be desired, but it seems like in the smaller villages –especially among indigenous communities– is non-existent. The teachers are known for beating the kids more than they tutor them. So some parents choose not to send them at all. Instead, they stay in the village and help with the work. The boys take the cattle to feed since they’re about 10 years old. The smallest ones help to get the little goats and sheep to safety, and they shadow their mothers when they go to milk the cows.

They’re sweet, lighthearted, curious, and full of energy. But also in desperate need of a proper school, where they can learn how to read, write and add things up, while preserving their Masai culture and traditions. Sadly, their only option is a Swahili school, the public one provided by the government that doesn’t consider their traditional way of life. Or an out-of-reach-for-their-budget private school in a village 10 km away.

They seem to have a happy childhood, free in the bush, with many cousins around to play. But in light of how the Masai’s traditional lifestyle is threatened, the future of these kids is uncertain, especially without education.

Rite of passage: men becoming warriors and girls becoming women (FGM in Masai culture)

*Quick disclaimer: none of the Masai ladies talked to me about this during my stay in the bush, but I think it’s worth mentioning it to understand the culture a bit better. My assessments are based on my research and overall knowledge in Human Rights Law. I have no firsthand information regarding Female Genital Modification (FGM) in Lesoit or anywhere else in Tanzania.

To initiate children into adulthood, the Masai conduct a genital modification ritual. The boys are circumcised, and they become Masai warriors. The girls should undergo a similar process to become Masai women –with a small cut in their clitoris. But under international pressure the Tanzanian government banned the practice. As this is an essential part of the culture, it didn’t stop.

The uncut girls will never be seen as grown women, so they will have issues finding a husband, and doing any decision-making, because no matter their age, they’re culturally still kids. The problem now is that, since the prohibition, the cuts are being done earlier to avoid being discovered and punished. And with this, infant girls are being considered women, so the marrying age is going down, with fathers marrying of their girls at a much younger age than a decade ago.

This is one of the many instances in which white saviorism turned to the worse. Don’t get me wrong, the harsh ways in which FGM is done in some places should be stopped, but in the Masai culture is a harmless equivalent to male circumcision, hence prohibiting it is yet another form of discrimination against women.

The few NGOs in Tanzania that actually work with the Masai women (instead of giving them a voice from a high horse without listening to them) are advocating for equality in rights, not changing gender roles. They don’t see FGM (or polygyny for that matter) as cultural oppression. In the insightful book Gender and Culture at the Limit of Rights, Dorothy Hodgson recounts her interpretation of what Masai women told her after years of field work with them:

“[…]the problems they face today are not inherent to their ‘cultures’ and ‘traditions’, but the product of brother political and economic forces such as colonialism, missionary evangelization, capitalist industry, the privatization of land and other natural resources, population pressures and HIV/AIDs that are depriving them of their lands and livelihoods and seriously eroding their rights. Even domestic violence and the ‘culture of patriarchy’ are understood as historically produced, linked to and articulated with conflict, violence and patriarchal orders occurring nationally, regionally and internationally”.

FGM is not a Masai problem, nor their women’s priority. Their urgent needs, she cites, are hunger, poverty, lack of access to clean water, land rights, education, and, for some, lack of access to health. It’s easy to judge genital modification from the west, being that it seems like a worthy cause, but those that really care should seek guidance from those that they’re trying to help in order to do it right.

Blood drinking

One of the things that people see in documentaries and wonder if it’s true is whether the Masai still drink blood. It seems hard to imagine nowadays someone drinking the warm blood of an animal that was just slaughtered. Well, they do. I’ve witnessed it.

The patriarch of the boma was ill during my stay in the bush. That meant that a sheep had to be killed. A medicine man from another boma was summoned, while a sheep had its last breaths. The warriors carefully took the leather, and then cut away the fat. While the medicine man started to melt the fat over a bonfire to make an oil for the patriarch, the young warriors continued butchering every single part of the animal.

When they opened the ribs and uncovered the blood, all of them came around it and grabbed handfuls that went straight to their mouths. The heart of the goat was eaten raw too. “Do you want to try it?”, told me a warrior while wiping his mouth. I’m willing to do a lot to have a new experience, but I draw the line with vegetarianism, so I profusely thanked him for offering me a chance to take part in a rite reserved for the men, but I settled for only witnessing it.

Another warrior appeared from the bush with some roots and shards of wood. He scratched pieces of them, and those were put to simmer with the oil. Once boiled, it was left to cool down, strained, and pass to the patriarch to drink. The ritual finished the next day, with him drinking an infusion made from the rest of the blood, the sheep’s head, and some bush herbs and roots.

The whole process was hypnotizing to watch, like a choreography: absolutely smooth, everyone aware of their role and of the timings. Even though it was hard for me to stomach the butchering of the poor sheep, it was an honor to be able to take part –even if just as a spectator– to such an event. And my apprehensions calmed down upon seeing how every single part of the animal was utilized. Unlike in the western world, nothing went to waste. It was actually funny that one of the elders, after tasting a part of the cooked stomach, was able to tell where the sheep had been drinking water, out of the amount of sand in it. Their ancient knowledge goes beyond what we, outsiders, can ever grasp.

The whole rite seemed to work: the patriarch is in his 70’s and healthy (when the life expectancy in the country is only 65 years of age).

It’s worth noting that the blood is drunk, like in many indigenous cultures, during rituals and celebrations, but also because of its nutrients, and as a source of calories. An academic paper describes it as “both ordinary and sacred food”. The blood is obtained not only by killing an animal. When a small quantity is needed, they nick the jugular artery of a cow, allowing blood-letting without slaughtering.

My take on the Masai after 2 months in Tanzania

My initial impression changed drastically, being now closer to how I feel about the indigenous peoples of my own country. The Masai are not rude or pushy, they are forced to be. They were left out of modern standards. They’re judged and misunderstood. Society failed them, and they’re reacting now however they can. After much of their ancestral land was taken, and many in the country look down at them as savages, they’re trying to cope and find a place where they belong. Some do it fighting to preserve their ancestral lifestyle. Others do it going to the cities to make some money to get drunk.

What saddens me is to witness how unaware they are about the importance of their tribe. Of course some are proud to be part of it, but most are oblivious on how their decisions affects the whole Masai community.

I asked Yayai, Stephanie’s mother-in-law, what she’d like for the world to know about Masai culture, and she couldn’t reply. As most Masai, she simply hasn’t thought about. She’s among the lucky ones that hasn’t seen her life affected by modernity, although she had to endure her sons going away to work (that’s how Stephanie met Sokoine, her husband, in Mafia Island). I then asked her what makes her happy. “My children and my cows”, she immediately replied, without thinking about it for a second.

Why is it important to preserve the lifestyle, traditions, and culture, you ask? It seems easier to make them assimilate to the rest of the country, send them to school, and move them to cities. Well, that would be terrible for the planet. The Maasai have been living with their cattle among wild animals for so many generations that they know how to care for the earth and wildlife like no one else could. And, as Yayai showed me with her answer, not only they know how to protect the earth, they also deeply care for it.

It’s hard to find a balance between preserving their culture (which in turn will help preserve nature and wildlife), and accepting that some Masai just want to live in modernity. I believe the key is in education. Not the western take on it, but one that can help them see they are unique, special, important. One that can give them tools to migrate to cities if they want to –basic skills like reading and writing, and fluency in Swahili and English languages; but most importantly that contributes to their traditional way of life: land management, sustainable sourcing and use of water, cattle caring, basics on business and administration.

But who am I to tell. The purpose of this post is not to give answers, but to narrate a cool story, and to create awareness on how threatened the lives of indigenous peoples are. If when you visit Tanzania you understand them more and judge them less, it was worth it.

When time to say goodbye came, I went to thank the women for welcoming me into their homes and lives. As we sat in a small hut full of smoke after dinner was prepared, I told them how grateful I felt to be invited to join their lifestyle. After putting up with me shadowing them for days, instead of being relieved to go back to normal, they were sad to see me go, and they apologized for not having a goodbye present. “I’m the one who’s sorry for not having something to give you”, I quickly said. One of the women took a necklace from the ones she was wearing and put it on my neck. That’s the kind of people they are, happy to share what they have.

It’s not easy to live in the bush –especially when you’re used to western standards. But it’s a beautiful life. The connection you can feel with the land and the people is impossible to find outside indigenous communities. And I’ll forever treasure being given the rare opportunity to experience it. I hope through this tale and pictures you felt there too.

A big big thank you to Stephanie Fuchs (@masai_story) for inviting me, guiding me, translating for me, feeding me, and –most importantly– allowing me to be part of her family for a few days. I’m in awe of her contribution towards awareness of the Masai culture, and I’m proud to be able to call her a friend.

WHAT TO READ NEXT?

- Reflections from the Serengeti: the Masai, sustainability, and decolonizing conservation

- Travel lessons: what visiting 50+ countries has taught me

- The ULTIMATE Travel Experiences Bucket List

- Does your place of birth determine who you are? A reflection on tourism, migration, and globalization

- Geopolitics of Travel: insights beyond what the media portrays

- Travel resources: the best travel tips and tricks

Liked it? Want to read it later? Pin it!

Did you like what you read? You can show your appreciation by buying me a coffee 🙂

Your support will ensure I keep bringing you stories and insights from around the world! Thanks so much!

What an incredible experience! You are so lucky to have been invited by Stephanie and her family. It’s really interesting to hear how it changed your perspective of the Masai culture.

We did visit a Masai village in Kenya. I loved meeting the ladies but it was all designed to show off for tourists (and to get some money out of us) I have always wondered what they think of the random westerners that they invite in for an afternoon. It felt both authentic and fake…but I guess it is similar to what you described. It was a group of people making the best of their situation and displaying their culture to make extra money on the side. It’s not that different from my Irish friends giving Irish dancing performances when we were kids to get extra money from the American tourists.

Anyway, thank you for sharing. This was a great read.

It’s so hard to find a balance! I’ve seen what you’re describing in some places around Tanzania, where a circus is being made out of their lives. I understand that it’s a great opportunity for them to make some money, but usually it’s not managed by them, so they get a fraction of the money charged, and they have to perform for the visitors, which I find terrible. If people were fine with just seeing the way of life, and taking pictures with whomever wanted to pose, then it’d be alright, but making them sing and dance, or stopping a class in a school so tourists can take a look is definitely not good. Hopefully it’ll develop into a sustainable tourism model, where they set their own rules, the money stays in the villages, and their traditions are culture are respected.

Oh, and I’m really happy to hear you enjoyed the read ❤️

Wow, parts of this story really break my heart. It’s so sad to see what colonialism and capitalism have done to cultures, but I’m glad to hear that there are some Masai still thriving despite the hardships. I’m so curious as to how Stephanie met her Masai husband!

They met because of the hardships the Masai are going through. He went to work to Mafia island to support his family, and she was there at the time, volunteering. They fell in love, and she moved to the bush. I don’t think if she sees it this way, but I believe it was amazing for the whole family that they got married. She’s encouraging them to keep embracing their traditional lifestyle, in a world where the younger ones are tired of how hard everything is for them, without seeing how hard it’d be if they leave the boma. They’re seeing the awesomeness of their culture through her eyes.

Wow, what an incredible and insightful experience! We visited Kenya early last year and were able to spend the afternoon with the Masai; it was a truly unique and interesting experience. We learned some of what you touched on here too! I can’t imagine spending as much time as you did. Truly incredible. Xx Sara

It was absolutely incredible. I’m truly grateful that I had the opportunity!

I don’t know how it is in Kenya to visit the Masai, but it sounds like it was a good experience. In Tanzania, sadly, in some places a circus is being made out of Masai life, charging big amounts that hardly reach the community, and making them dance and sing for every group of tourist approaching, who are not interested on learning, just about the photo op. That’s especially why I’m so thankful to have been able to experience it in this real way 🙂

I’ve been beating myself up silly since 2015 for going to Kenya and completely missing out on Masai Mara.. thank you for this and definitely going to give it a second look!

I don’t know how much of Masai life you can see in Masai Mara, but for sure the park is a must in Kenya. I haven’t been, but it’s the continuation across the border from Serengeti, so it has to be amazing. Well, there’s always next time 🙂